Community engagement, co-design, and sustainable food

By Sara Heitlinger, Queen Mary University of London

How can digital and networked technologies support more sustainable food practices in the city?

Over the last year and a half we have attempted to answer this question in a research project called Connected Seeds and Sensors by working with seed-savers – or Seed Guardians – to co-create a Connected Seeds Library, owned and maintained by the community at Spitalfields City Farm.

This website forms one of the final outputs (alongside an exhibition, a documentary film, a book, and an interactive seed library) from the project. It includes essays, growing information and stories about the crops grown for the library, and experiences from Seed Guardians.

Seed Guardians

Throughout the 2016 growing season, fourteen Seed Guardians – people around east London from all walks of life – committed to grow one or two crops from seed, and to donate some of the seeds they would collect at the end of the season to the Connected Seeds Library. They have come from all walks of life, different cultural backgrounds, and with varying levels of gardening experience. Countries of origin include: Bangladesh, the Caribbean, Turkey, Zimbabwe, Ireland, France and England. Many of the Seed Guardians have no garden of their own, but by volunteering at community growing spaces such as Spitalfields City Farm, or carving out small plots on the communal land of the housing estates where they live, they have succeeding in growing their own food.

Seed Guardians were given digital cameras and a notebook, and were asked to document the growth of their plants throughout the life cycle, from the moment they sowed their seeds, to when they harvested crops and seed at the completion of the cycle. In this book you can read about their experiences, motivations, values, rewards and challenges of small-scale urban farming and seed-saving, gleaned from interviews conducted with the guardian-participants as part of the research process.

At the same time we built and deployed networked environmental sensing devices that measure the environmental conditions under which the plants were grown, as a way of exploring the potential value such technology could provide to the community. Hamed Haddadi discusses some of the challenges and opportunities of working with these sensors.

There were many challenges to conducting our community research. It required the committed engagement of diverse participants, located across many geographical locations, over many months. One participant was given notice on his house and had to move to another part of London, forced to give his plants away. Others spent the crucial summer months abroad to help aging and ill relatives. One became a parent for the first time, while another’s job became all-consuming. Gardens took a back seat as life got in the way.

There were also challenges inside the gardens, typical of small-scale and community agriculture that makes a commitment to eschewing chemical fertilisers and pesticides. Crops failed due to pests, but also because of the vagaries of an uncertain climate. This unpredictability is set to increase with climate change. Therefore it is ever more important for growers to have access to locally-grown and adapted seed, that is viable and resilient for local conditions.

This is precisely what the Connected Seeds Library offers: dozens of seeds from crops, many of which are not typically grown in the UK, held in commons as a free resource for the community. But not only do we have the seeds, we also have records of the experiences and knowledge of the people who grew them.

The seeds alone form a treasure chest of the highest value, able to sustain many people. The records that accompany them makes them even richer.

Despite the challenges of small-scale and community urban food-growing and seed-saving, the rewards are clear, and run in threads throughout this book. One thread relates to the positive contribution gardening has on Guardians’ mental and physical health, whether as a de-stress, through eating healthy fresh food, or gentle physical exercise. Another thread draws attention to the social benefits that arise through gift exchange of seeds and other garden produce, or by helping Guardians overcome social isolation and cultural barriers, and connecting them with neighbours and family members across generations. These activities have afforded a sense of agency and control over Guardians’ lives by saving them money and reducing reliance on corporations.

Co-designing With the Community

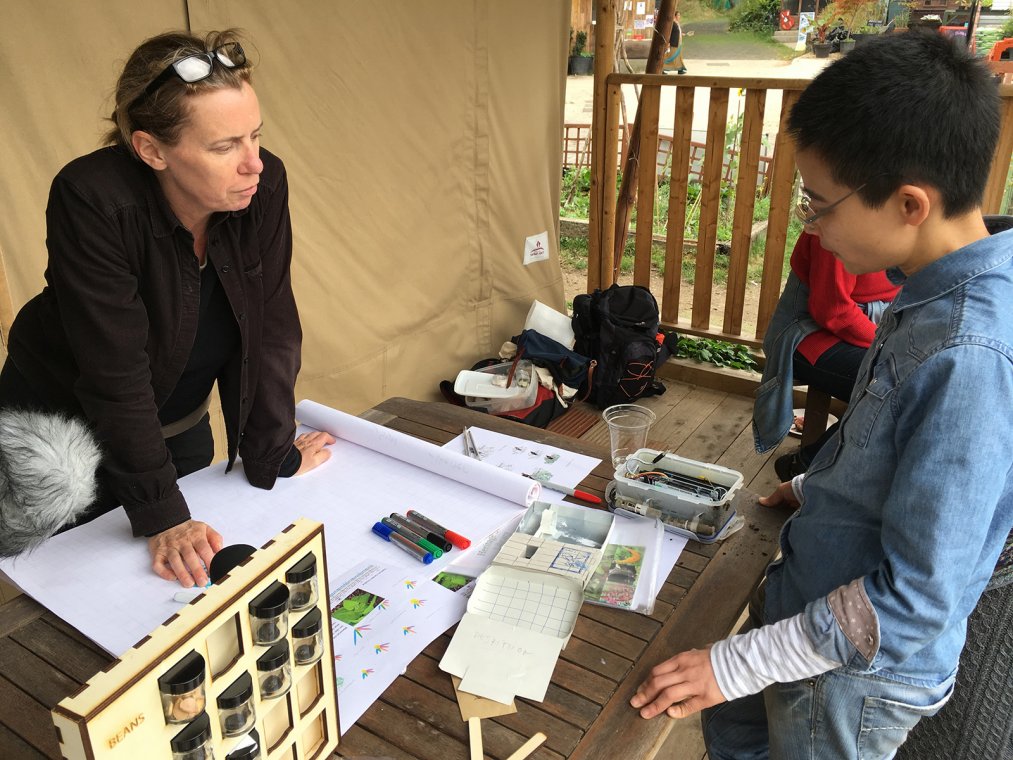

Discourses around technology design, particularly in the emerging domains of “smart” sustainable cities and Internet of Things (IoT) – see Hamed Haddadi’s writing and Carl DiSalvo’s piece for more on this – are often about automating processes, making them more efficient and therefore more sustainable. But what values are we compromising if we automate small-scale and community gardening? The people we worked with don’t want to forego a connection with the land, nor the labour and care that goes into tending their gardens. They don’t want to lose opportunities for face-to-face communication. How, then, can we design technologies to bring people together, to learn from each other, to share, and meet in physical space? We can begin to answer this question by involving the people who will be affected by the designs, into the design process itself.

During previous research at Spitalfields City Farm (conducted during my PhD), it became apparent that there is immensely rich and diverse knowledge around food-growing from around the world that is collectively held by the local community, but there are many challenges for accessing and disseminating this knowledge. Together with farm staff we developed the idea for the Connected Seeds Library, as a way for digital technologies to help collect and share this knowledge.

At the start of the Connected Seeds and Sensors research we organised a number of workshops with the farm community to understand the needs, practices and values of small-scale and community urban growers and seed-savers. We also organised various events throughout the growing season, including seed-swaps, seed-saving workshops, garden visits and design sessions. The aim of these activities was to support a community of practice, where people could share skills and knowledge. Another aim was for the research team to gain an understanding of how future technology design could be grounded in the needs, practices and values of these communities.

The Connected Seeds Library

The Connected Seeds Library is the outcome of this process. Visitors to the library can join for free and take some seeds home to grow. They are encouraged to keep some of the harvest for themselves, and to bring some seeds back to the library at the end of the season, thereby ensuring that living stock is maintained.

The Connected Seeds Library celebrates the diversity of urban food-growing and seed-saving practices

The library itself is augmented with digital technology: a seed variety can be selected and then placed on a special pad, which triggers a slideshow to play on a screen, showing images of the chosen plant. Visitors then have the option of turning a wooden wheel to hear, over a loudspeaker hidden inside the library cabinet, the voice of the Seed Guardian who donated that seed, talking about their experiences of growing. If the visitor turns the wheel, they will get the next instalment of the story, and in this way they can access different types of content relating to the motivations, experiences, lessons learnt and food recipes from the Guardian.

The Connected Seeds Library was designed as an engaging, interactive and playful artefact that does not require any particular technical skill or ownership of smartphone or computer. It is intended as an educational resource for the farm, with the aim of drawing in new audiences and visitors, and sharing and celebrating the diversity of urban food-growing and seed-saving practices with a wider public. In particular, we hope it will increase skill and knowledge of growing “exotic” crops (i.e. not typically grown in the UK), which are in particular demand in this part of the country due to large scale immigration and ethnic diversity. In turn, we hope that this will empower communities by connecting them to their heritage through stories around food. It will decrease their reliance on consuming shop-bought produce thereby saving them money, as well as contribute to a healthy diet of freshly grown local vegetables. In addition to contributing to biodiversity, it is my hope that the library will inspire people to grow their own food, thereby reducing the CO2 emissions of food that must travel large distances from the site of production to the shop shelf.

In these ways, Connected Seeds and Sensors, and other research projects like it, have the potential to positively impact on environmental sustainability, social inclusion, and healthier, more resilient urban communities.