What else might a smart city be?

By Carl DiSalvo, Georgia Institute of Technology

Nearly every player in the technology sector has made a claim to Smart Cities, from providing end-user services to global infrastructures and everything imaginable in-between. Cisco, IBM, Siemens, and many others have presented us with their visions of Smart Cities in whitepapers, concept videos, and demos. Of course, these visions are malleable and are made to adapt as changes occur in science, in policy, and in politics. But across and throughout, these visions hold fast to common ideals of control and efficiency. These ideals and their attendant practices and techniques have a long history in city planning and connect to histories such as those of cybernetics and other varieties of systems science. The primary visions of Smart Cities are thus, unsurprisingly, mostly just updated versions of logistics and supply chains applied to cities and civics.

It’s not as if design has been absent from this affair. Designers from all fields actively participate in crafting these visions of Smart Cities. The images, diagrams, animations, and prototypes that express the prevailing visions of Smart Cities are compelling precisely because of the quality of design thinking and making that goes into their production. Indeed, Smart Cities, as we are coming to know them, may be exemplars of a new kind of total design, which attempts to fold together information, environment, and experience in previously impossible detail, to produce an absolutely mediated civics.

If we have an interest in other forms of cities, other configurations of public life, then it seems the question is no longer “What is a Smart City?” but rather, “What else might a Smart City be, or become?”

If we want Smart Cities to be something else, or to be something more, something in addition too, then we don’t just need more design, what we need is a different design.

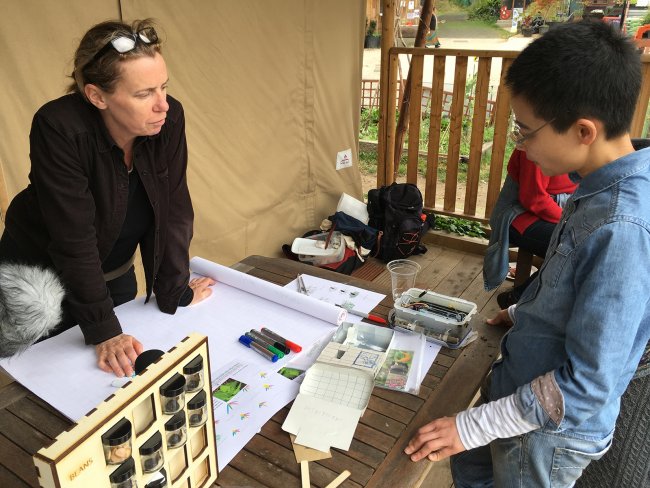

Participatory design—particularly as exemplified in the Connected Seeds and Sensors project—offers us one way of doing design differently. The origins of participatory design are in the shop floor, engaging and collaborating with workers to strive towards a more democratic workplace, which values the skills of labor and the tools workers use to express those skills. Contemporary participatory design, in many ways, retains these motivations, albeit in new contexts and practices that express the changing landscape of labor, which includes knowledge workers, the creative industries, diverse and community economies, and even citizenship. Affect and precarity characterize these new conditions. What participatory design offers is a commitment in the form of a practice, a commitment to workers and labor, a commitment to endeavoring together with, to collectively strive for possibilities and potentials rooted in the desires and capacities of those who are doing the work—whatever that work might be.

And make no mistake, despite all sorts of claims about automation, Smart Cities are sites of labor and require work in order to function. One question to ask is “How can we bring those whose work it will be to build, use, and maintain the Smart City into the design process?” Another question to ask is “What new forms of labor might emerge in Smart Cities, and how might we design, together, in anticipation of those new forms of labor?” And yet another question to ask is “What kinds of work are being overlooked in the rush to make cities smart, and how might the technologies and services of Smart Cities affect these ignored or disregarded sites and practices?”

Small-scale agriculture, gardening, foraging, and other forms of diverse agricultures and community food systems are examples of the kind of work largely being overlooked. Yes, there is some attention given to these topics and how they might become “smart”—as food culture possesses a certain cache´ in the moment—but that attention fades as we move beyond the star chef or starred restaurant. Rather than generically romanticizing the “small” and “alternative” we should attend much more closely to the particularities of these sites and most of all to the work of these practices. Sensing and automation, data mining and machine learning and other technologies of Smart Cities may have a role to play in diverse agricultures and community food systems. Perhaps even more provocatively, small-scale agriculture, gardening, foraging and the like may be able to contribute insights into the building, use, and maintenance of Smart Cities. After all, these sites and practices are lasting examples of an inventiveness that manipulates and exceeds the standard logics of the built environment toward other desires. What is the skilled work of these diverse agricultures and community food systems? How will the labor of cultivation and care, of providing for self and others, of building and sustaining belonging, be affected by the structures and infrastructure of Smart Cities? How might we envision services as tools of value to these practices?

Answering these questions is an important endeavor, which design can, and should contribute to. The answers cannot come from designers alone. In fact, it’s not even certain that designers should take the lead. And this is where a participatory approach to design is of such great value. What design can offer are methods and techniques for elicitation, representation, and performance. What design can offer are compelling modes of enactment that—like the more common visions of Smart Cities—can lure us into considering, perhaps event wanting, a Smart City, but in these cases, a different notion of what a Smart City might become.

This is the value and importance of projects such as Connected Seeds and Sensors. We will not, through design or other means, soon replace the modern city. We will not thwart or oust those technologies of monitoring and prediction that Smart Cities are bringing into being. But, through other approaches to design, we may be able, together, to support a more pluralistic notion of what we want our cities and our civics to be like in the 21st Century — how we want, and might be able, to imagine and enable the skilled work of togetherness.